How to understand and solve Leontief input-output model (technology matrix) problems

Courses: M118, MATH135, V118, D117

Posted by: Alex

Today, let's take a look at everyone's favorite matrix application problem, Leontief input-output models. You might know them simply as "technology matrix" problems, but actually the technology matrix is only one part of the problem. The really interesting part is in the derivation of the matrix equation - something that most finite math courses seem to gloss over in the end-of-semester frenzy.

So, let's take a look at a typical "technology matrix" problem, and see if we can't understand how the problem actually works. Hopefully, it will make it easier to remember than an arbitrary formula.

Example: An economy consists of two codependent industries - steel and lumber. It takes 0.1 units of steel and 0.5 units of lumber to make each unit of steel. It takes 0.2 units of steel and 0.0 units of lumber to make each unit of lumber. The economy will export \(16\) units of steel and 8 units of lumber next month. How many units of steel and lumber will they need to product to meet this external demand?

The crucial thing to understand about these problems is that both industries need some of each product (possibly including their own) to make more of that product. It's the old "you gotta spend money to make money" routine. So, in order to make steel, the steel plant needs a little bit of steel (hopefully less than it is producing), along with some lumber. The lumberyard also needs some steel and lumber to make more lumber. This might be particularly relatable if you've ever played a game that involves gathering and spending resources, like Age of Empires or Settlers of Catan.

The next thing to understand is that the problem is asking us for how much of each resource we need to produce - which will be more than the amount we're exporting. Why? Because some of the steel and lumber we produce goes back into the two industries to meet the production (which itself requires some steel and lumber, and so on).

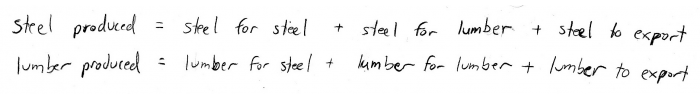

For both resources, the production can be broken into three parts:

- The amount of the same resource needed to produce more of the resource;

- The amount of the other resource needed to produce more of the resource;

- The amount of the resource we need to have left over to export.

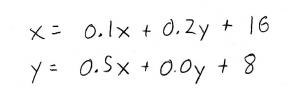

In the case of our steel-and-lumber operation, we can write two equations:

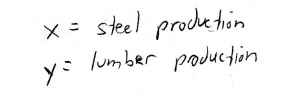

Next, let's try to write these equations more mathematically. The problem tells us to define \(x\) and \(y\) such that:

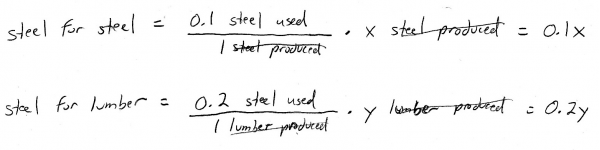

Now, let's figure out expressions for the total steel needed for production of more steel and lumber. These are going to depend on \(x\) and \(y\), since \(x\) and \(y\) represent the amount of steel and lumber we're producing. Well, the problem tells us that it takes 0.1 units of steel for each unit of steel, and 0.2 units of steel for each unit of lumber:

So notice that by dimensional analysis, both of these terms are referring to an amount of steel.

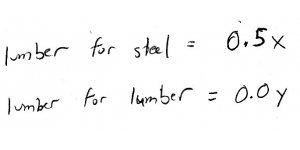

We can use the same thought process to find the amounts of lumber needed for producing steel and lumber:

Substituting these expressions, along with the external demands, into our overall production equations, we get:

Notice that the first equation says that the total amount of steel we need to produce \((x)\) depends on itself \((0.1x)\), as well as the total amount of lumber we need to produce \((0.2y)\) and the amount we need to export (\(16)\).

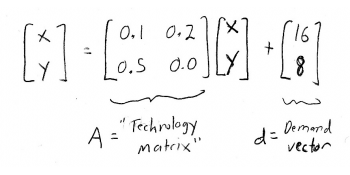

Great, we've turned our problem into math! But, how do we solve it? Well, these are matrix application problems, after all. So let's rewrite this system of equations as a matrix equation:

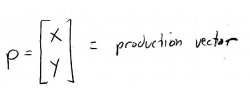

Matrix \(A\) is now our infamous "technology matrix", and the vector \(d\) is the demand vector. We can also define a production vector:

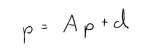

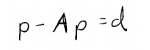

We can thus write our equation more compactly:

where our goal will be to solve for \(p\). How do we do this? Well, it's (almost) like solving a regular, non-matrix equation - we need to group like terms.

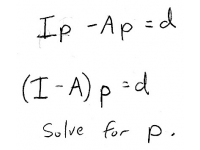

The only question is, how do we group those like terms? Well normally, we'd factor out the \(p\) from both terms, and we'd have \((1-A)p\). The only problem is that we can't subtract \(A\) (which is a matrix) from the number 1 (which is not a matrix). We need to use the "matrix equivalent" of the number 1 - the identity matrix!

With the 2x2 identity matrix, we can now write:

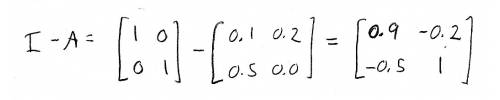

We already know \(A\), so we can find \((I-A)\) by subtracting the corresponding elements:

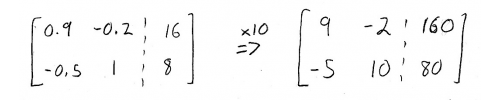

We also know \(d\), the demand vector, so we can set up an augmented matrix that lets us solve for \(p\):

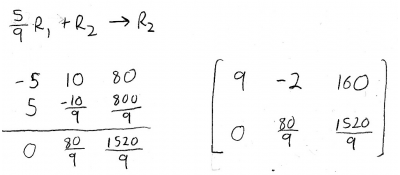

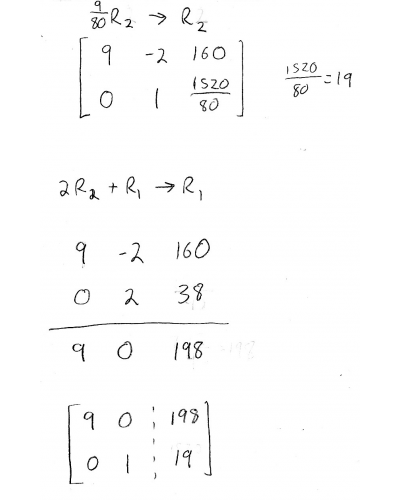

We'll multiply the whole thing by 10, to make the arithmetic a little bit easier. Now, we can start performing row operations to solve the augmented matrix:

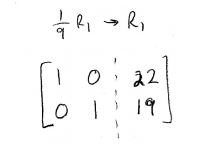

And finally,

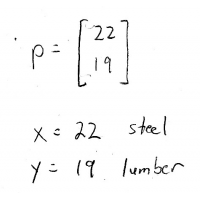

So now, the right-hand column has the solution for \(p\)!

I hope this made sense, and good luck on finals!